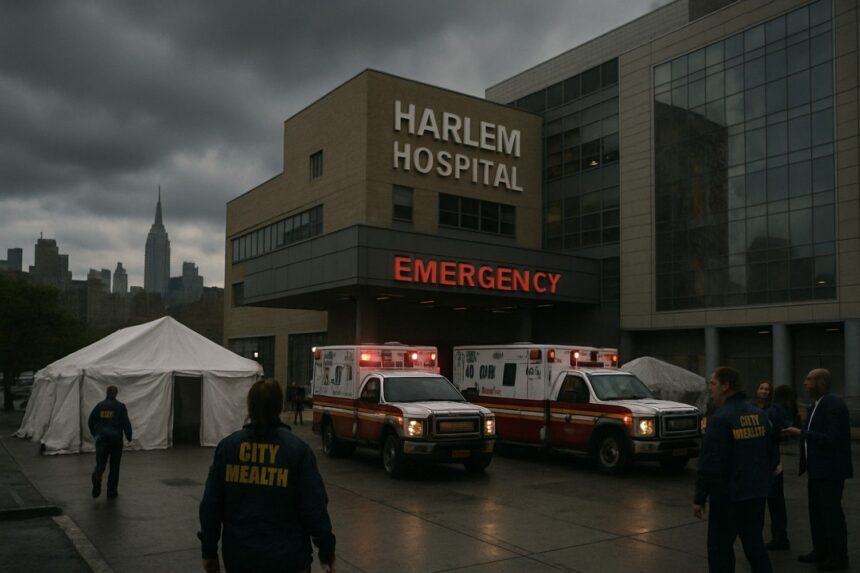

In an alarming public health crisis, New York City officials have declared the recent Legionnaires’ disease outbreak in Harlem officially over, marking the end of a deadly surge that claimed seven lives and sickened over 100 residents. The outbreak, which began earlier this summer, was ultimately traced to cooling towers at the city-run Harlem Hospital and another municipal facility, prompting widespread concern and calls for tighter safety regulations.

The rapid escalation of cases was first detected in July, as hospitals and local clinics reported a steady stream of patients presenting with high fever, chills, and respiratory distress—symptoms characteristic of Legionnaires’ disease. City health officials, led by Dr. Ashwin Vasan, confirmed that contaminated water vapor from hospital cooling towers enabled the Legionella bacteria to spread through the Central Harlem community, resulting in 114 confirmed cases before the situation was contained.

“Losing seven neighbors is devastating,” said Harlem local Mary Jenkins, whose apartment is just blocks from the hospital. “We need better oversight, because this should have never happened.” Hospital representatives and city authorities have faced mounting criticism for delayed inspections and lack of communication between agencies responsible for public health

In response, Mayor Eric Adams announced immediate changes to municipal regulations, including more frequent monitoring of cooling towers and mandatory public notification in the event of any environmental health threat. “Our city’s commitment is to prevent another tragedy like this,” Adams said in a press conference Friday.

Public health experts warn that while Legionnaires’ disease is not spread person-to-person, elderly individuals and those with compromised immune systems remain highly vulnerable. The CDC reports annual outbreaks in major U.S. cities, but NYC’s tragedy drew attention because of its scale, the hospital link, and the failure to act on early warning signs.

As investigations continue, many local residents are left questioning systemic accountability. The New York Department of Health has pledged a full review of city-owned facilities, and legal actions by victims’ families could reshape standards for hospital maintenance citywide.

NYC is now at a crossroads: as the city mourns its losses, it must rebuild trust in its public health infrastructure—ensuring that negligence never again leads to deadly consequences.

Symptoms of Legionnaires’ Disease

Legionnaires’ disease is a severe type of pneumonia caused by Legionella bacteria. Symptoms usually start 2 to 10 days after exposure and often begin with flu-like signs such as:

- High fever (up to 104°F or 40°C) and chills

- Headache and muscle aches

- Cough, which may produce mucus and sometimes blood

- Shortness of breath and chest pain

- Fatigue and muscle weakness

- Gastrointestinal symptoms like nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea

- Confusion or other changes in mental status in severe cases

Unlike typical pneumonia, Legionnaires’ may also present with diarrhea and hyponatremia (low sodium levels), which can aid diagnosis.

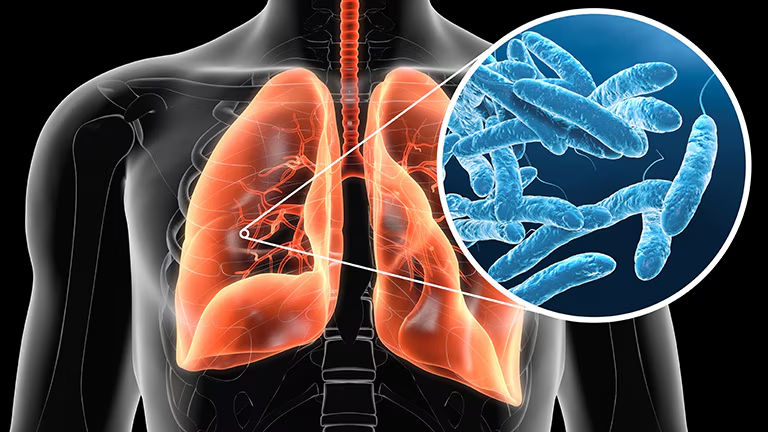

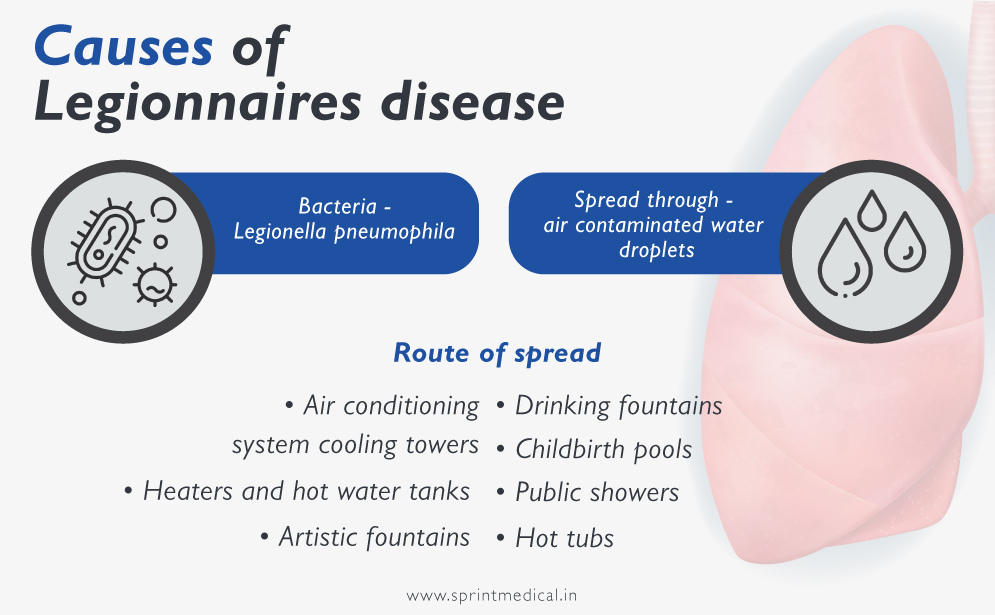

Causes of Legionnaires’ Disease

Legionnaires’ disease is caused by breathing in aerosolized water droplets contaminated with Legionella bacteria. Common sources include:

- Cooling towers (as in the recent NYC outbreak)

- Hot tubs and spas

- Large plumbing systems in buildings

- Decorative fountains and water features

The bacteria thrive in warm, stagnant water and can spread when contaminated water is aerosolized into fine droplets suitable for inhalation. People at higher risk include older adults (over 50), smokers, those with chronic lung disease, or weakened immune systems.

Treatments for Legionnaires’ Disease

Legionnaires’ disease is primarily treated with antibiotics effective against intracellular bacteria. Common antibiotics include:

- Azithromycin

- Levofloxacin

- Doxycycline

Early antibiotic treatment is crucial to reduce the risk of severe complications such as respiratory failure, sepsis, and kidney failure. Severe cases often require hospitalization, oxygen therapy, intravenous fluids for hydration, and sometimes ventilator support. Supportive care is important for managing symptoms and monitoring organ function.

A milder related illness called Pontiac fever, caused by the same bacteria, usually resolves on its own without antibiotic treatment.